During the COVID-19 pandemic, people spent a lot of time isolated and indoors, which helped foster an environment where some people now feel lonelier than ever. The result is a loss of social connectedness—the degree to which people feel the social connections and relationships in their lives to satisfy their wants and needs. When social…

Your Welcoa membership has expired.

Autonomy: What Wellness Needs to Learn from Business (and quickly!)

Dr. Jon Robison at salveopartners.com

Autonomy is defined in the dictionary as: “Independence or freedom, as of the will or one’s actions”

And though we often think of the “freedom” to act or the notion of “free will” from political or spiritual perspectives, some biologists now believe that it is an underlying and inalienable condition of life.

“The freedom to create one’s self is the foundational freedom of all life. One current definition of “life” in biology is that something is alive if it is capable of producing itself… Every living being is author of its own existence, and continues to create itself through its entire life span…Life gives to itself the freedom to become, and without that freedom to create there is no life.”

And according to Edward Deci, perhaps the world’s leading expert on motivation, autonomy is (along with competence and relatedness) one of three innate human psychological needs. A wealth of research, spanning many decades and from all corners of the globe, strongly supports that people naturally seek autonomy. When they find it their quality of life improves: better grades, increased persistence towards desired goals, higher productivity, less burnout and greater levels of psychological wellbeing.

In fact, the research is consistently clear that autonomy, the freedom people have to act, is a major determinant of human health. As world renowned epidemiologist and public health researcher Dr. Michael Marmot writes in his groundbreaking book The Status Syndrome:

“Autonomy – how much control you have over your Life – and the opportunities you have for full social engagement and participation are crucial for health, well-being and longevity.”

Autonomy in Business

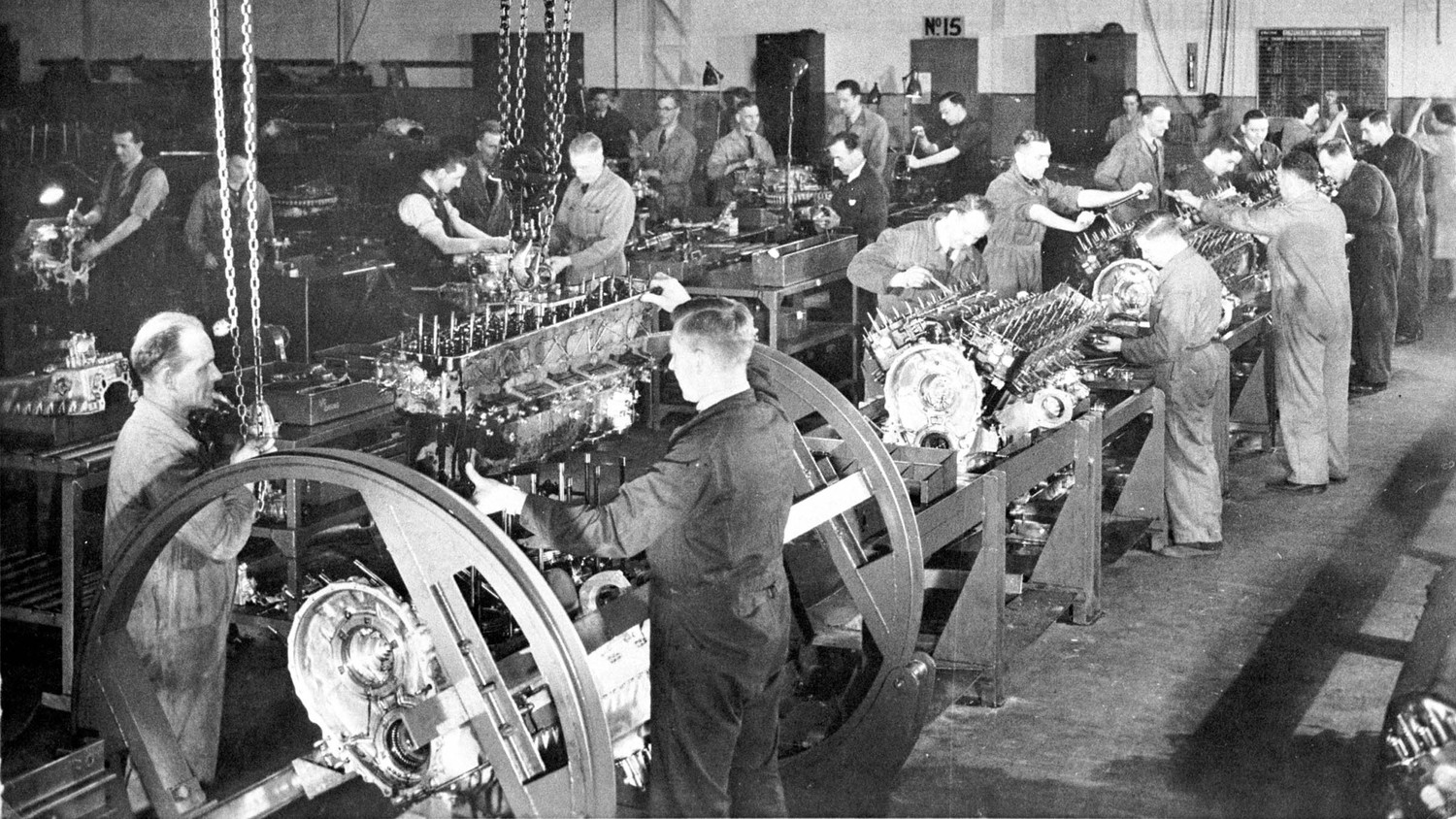

Then: In the late 1880’s and early 1900’s, Frederick Taylor introduced scientific management into the workplace. Taylor employed the same approach to improving the efficiency of employees as he did to the machines on which they were working. He broke job tasks down to their component parts and calculated the one best way to do the job. Echoing the philosophic footsteps of BF Skinner and other behaviorists, Taylor believed that working men’s minds were inconsequential, so that:

“Each man must give up his own particular way of doing things, adapt his methods to the many new standards, and grow accustomed to receiving and obeying instructions, covering details large and small, which in the past had been left to individual judgment. The workmen are to do as they are told.”

True to the legacy of the 17th-century mechanistic, reductionist worldview, viewing people as machines and applying similar scientific methods to human work gained great popularity among managers. As a result, early 20th century workplaces were painfully devoid of worker autonomy.

It is not difficult to pick out the flaws in this control-oriented approach to managing employees. We know that people want and need autonomy, responsibility and control over their work and the freedom to think and do for themselves. But when we separate thinking from doing, we severely limit their autonomy.

And Now: The good news for business is that experts in the organizational development world are keenly aware of the critical importance of worker autonomy. More than a decade ago, business management guru Peter Drucker put it best when discussing the importance of embracing the concept of worker autonomy:

“The need to manage oneself is therefore creating a revolution in human affairs.”

In fact, the most successful organizations today have fully and sometimes radically embraced the critical importance of worker autonomy. The Firms of Endearment (FoEs) are 28 widely loved companies including among others; Whole Foods, FedEx, Starbucks, Google, Southwest Airlines, Patagonia, Costco, Toms, Wegmans, Semco and Zappos. Among other distinguishing characteristics, these highly successful companies are benefiting financially by placing more autonomy in the hands of their employees because they have learned that when employees are engaged and fulfilled they transfer those qualities to their work

Here are just a few of the scores of examples provided in the book that demonstrate the amazing approaches these companies take when it comes to nurturing employee autonomy.

- At Wegmans food markets all employees have complete freedom to do whatever it takes to satisfy their customers – without having to consult with a manager; from cooking a Thanksgiving turkey in the store for a customer who had bought one that was too big to cook at home to sending a chef to a customer’s house to make right a food order that had been botched.

- At Brazilian ship building giant Semco: all meetings are optional (people are encouraged to leave when they lose interest), all vacations are mandatory; employees suggest their own pay levels, assess the performance of their bosses, and the books are open for all employees to see

- At Honda, any employee can invoke a meeting practice called waigaya (“noisy loud”), in which participants put aside rank to work on a particular problem – an invitation that executives must accept if they are called on to do so. At one such meeting a low-ranking employee was able to convince senior managers who wanted a more conservative approach that that the advertising campaign – “You Meet The Nicest People in a Honda” was a good idea.

Just to be clear, for those of you who might wondering how all this touchy-feely stuff impacts the bottom line, FoEs have outperformed the S&P 500 by a factor of 14 times over a period of 15 years. Without exception, these companies are, in more scientific terms, seriously kicking the butt of the competition in almost every imaginable way.

Finally, a growing group of self-managed companies has taken employee autonomy one giant step farther, doing away with the pyramidal hierarchies of power, and relocating most decision-making authority to teams of individuals – usually those closest to where the actual work is being done. From healthcare to education to manufacturing and from for profit to nonprofit, the resulting freedom and trust in individual autonomy has created innovative, progressive, highly successful (and profitable when appropriate) organizations.

Autonomy and Workplace Wellness

Then: Not surprisingly, like all other aspects of our culture, the wellness industry has its roots in the mechanistic worldview of the 17th century and the behaviorist dogma of the 20th century. Taylor’s belief in the inconsequential nature of human thinking and autonomy was echoed by the behaviorists most well-known advocate B.F. Skinner when he said:

”There is no place in the scientific analysis of behavior for a mind or a self.”

Although all of Skinner’s research was performed on animals, he believed that all human actions could be explained by the principle of “reinforcement.” This is closely akin to what we commonly think of as reward. Skinner’s theory states most basically that behaviors followed by rewards (positive consequences) are likely to be repeated. So, for instance, when the phone rings, we pick it up. If every time the phone rings we pick it up and nobody is there, we will eventually stop picking up the phone. Thus, the behavior of answering the phone is reinforced by the consequence of human contact on the other end.

Although this example seems reasonable, remember that Skinner believed that all human actions resulted from this same process. He concluded that human beings (like the machines on which they work and the rodents in his experiments) have essentially no freedom to act, no free will, no autonomy; that all our actions are merely mindless “repertoires of behavior” that can be fully explained by the environmental consequences that follow them.

Skinner was so confident in this theory of human behavior he felt it explained even the most complicated human experiences. In his own words, he describes the evolution of love between two people:

“One of them is nice to the other and predisposes the other to be nice to him and that makes him even more likely to be nice. It goes back and forth and it may reach the point at which they are very highly disposed to do nice things to the other and not to hurt and I suppose this is what would be called being in love.”

Now: Unfortunately, workplace wellness has not seen the same movement away from these outdated approaches to human motivation and behavior. In fact, a strong case can be made that, in terms of promoting employee autonomy, the industry has been moving in the opposite and wrong direction.

The movement backwards was given a strong shot in the arm by the passage of the so-called Safeway Amendment in the Affordable Care Act. While the use of incentives to “drive” employee health behavior had been present before, the ACA now gave permission for organizations to ramp up the intensity, not only to reward people for participating, but to punish them as well if they don’t – or if they do participate but fail to reach some predetermined health objective.

Participation in workplace wellness programs has always been problematic, so the justification for these incentives was that employees would not participate or improve their health unless they were forced to do so. While it is true that participation did increase some with the advent of these external rewards and punishments, the reality is that as Daniel Pink clarifies in his groundbreaking book, Drive: The Surprising Truth about What Motivates Us:

“The opposite of autonomy is control. And since they sit at different poles of the behavioral compass, they point us towards different directions. Control leads to compliance; autonomy leads to engagement.”

The results of this “wellness or else” approach to employee health have been devastating. Independent research has shown these programs don’t save money or improve health and they are highly disliked by employees, suggesting that they are more likely to decrease rather than increase employee morale and engagement which costs business a half a trillion dollars every year in the US alone. In fact even HERO, the major research arm of the industry has admitted that employee morale is a likely casualty of these approaches.

Even more discouragingly, perhaps in desperation to increase participation, some in the industry have recommended even stronger control-oriented strategies. It has been suggested that we need to be more authoritative in our efforts to control employee’s behavior; further reducing employee autonomy by “getting tougher” on them, jacking up the penalties and even making participation mandatory – with one wellness professional suggesting that employees who don’t like the programs might consider finding work elsewhere.

And in a recent, truly frightening editorial in the leading industry journal, it was even suggested that the best way to deal with employee health issues might be for business to simply not hire anyone who doesn’t meet some established health criteria for fitness, weight, smoking and who knows what else.

Take Home – Catching Up

It is increasingly clear that people and organizations thrive when autonomy is high, when employees are trusted and encouraged to bring their whole, unfettered selves to bear on their work and their work relationships. The workplace wellness industry’s movement backwards to the control-oriented approaches of the 20th century stands in direct contradiction to the ongoing revolution in organizational development and simply will not fly in the emerging volatile business landscape of the 21st Century VUCA world.

Many businesses and business leaders are already questioning these approaches as it becomes clear that they may well be detrimental to the successful direction in which their organizations are moving – and from which they are thriving.

For employee wellness to thrive and perhaps even survive, it is essential that the industry bring its understanding of human behavior and change into the 21st century. We need to put down our carrots and our sticks, embrace and nurture autonomy as a fundamental right of every human being and invest in our employees with a firm and sacred understanding that:

“The only way to achieve the goal of having employees act like creative, thinking, responsible, autonomous adults is to treat them like that is exactly what they are.”

It long past time to stop treating employees like they are cogs in a machine, small rodents or young children. Our industry leaders could learn so much from business people like Ricardo Semler, CEO of Semco, one of the wildly successful Firms of Endearment:

“We always assume that we’re dealing with responsible adults, which we are. And when you start treating employees like adolescents…that’s when you start to bring out the adolescent in people.”

NOTE: If these types of discussions inspire you, and if you want to do more hands-on work towards updating our approaches to organizational and employee wellbeing, please consider registering for Dr. Rosie Ward’s and my pre-conference workshop, Ushering Wellbeing Into the 21st Century: What We Need to Learn from Business (And Quickly!), at the upcoming WELCOA Summit in Omaha, NE on August 28, 2017 from 9 a.m. – 4 p.m.

We would love to see you there to join with us in building a community of “paradigm pioneers.”

Sincerely, Dr. Jon